You Can’t Learn from the Past

The Halloween Sideshow, 2022

Trevor Ritland

THE OLD TIME TRAVELER sat in the library of a Manhattan social club, where a satisfied fire chewed at the bones of dark logs in a stone hearth by the window. The window was open, allowing an icy breeze to blow in from the street below. It was October the twenty-fifth, 1964.

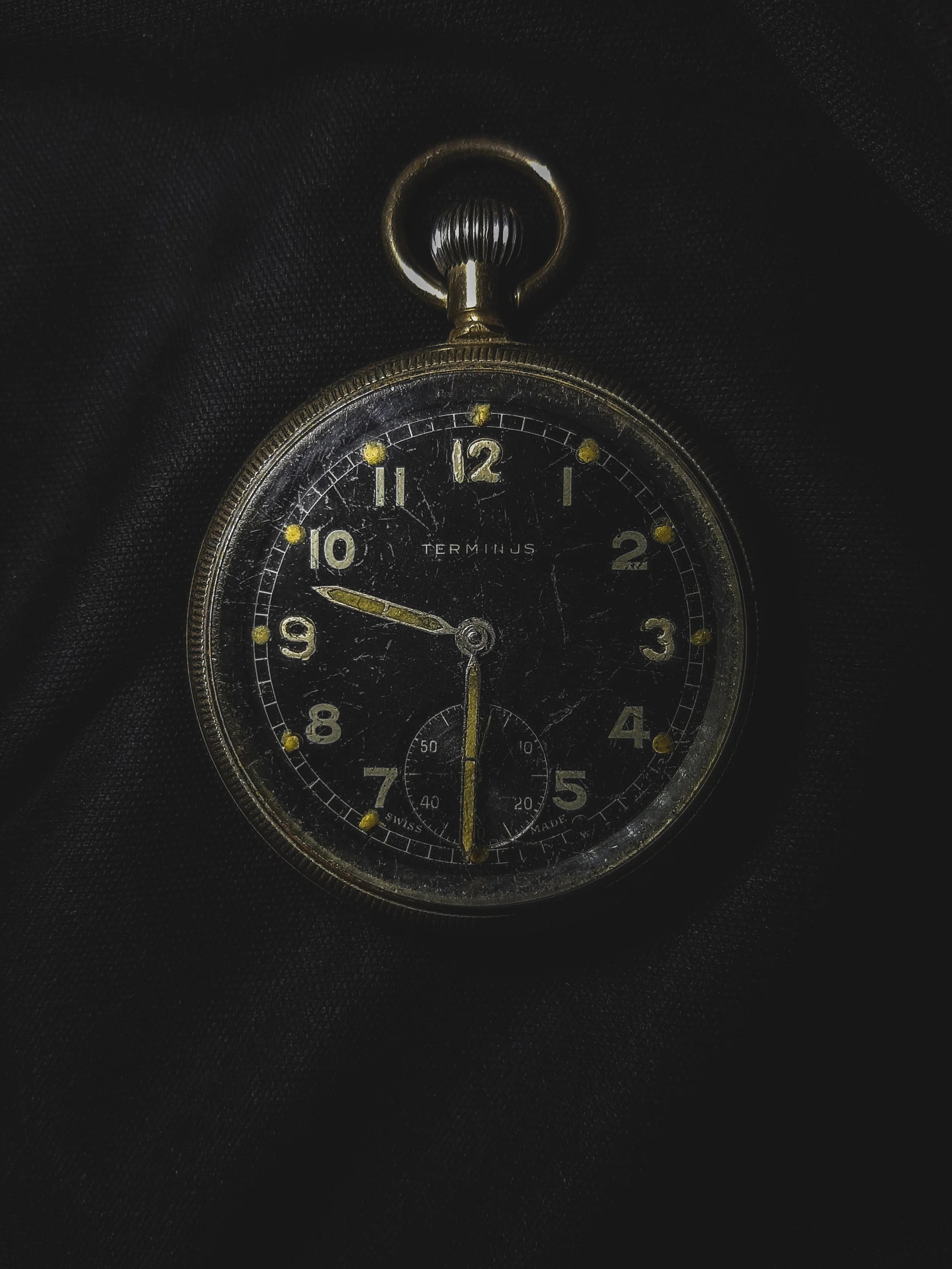

Outside, snow was drifting over the city aimlessly, not in any hurry. The time-traveler watched the light flakes dance against the dark city from where he sat by the fire, holding a book in his lap but not reading. The walls of the room were lined with bookshelves; it was the reading room, where the city’s prosperous men retreated on cold nights at the edge of winter to drink warm liquors and trade tales like chess pieces. The time-traveler was not drinking or smoking. He looked alternatingly at a pocket watch that he kept on a silver chain, and at the door. It was seven-thirty-two, eastern standard time.

The time-traveler was not alone in the library (though it would not reach its full capacity for at least another hour); two young men played cards at a table by the foyer, and an older gentleman stood at the bar pouring himself a glass of bourbon. From the next room, the voices of three or four men just arriving could be heard. Also, an attendant came in and out of the room occasionally, freshening drinks or bringing cigars, and now had stopped to talk with the man at the bar in soft and conspiratorial tones.

Beneath his overcoat, which he wore despite the warmth of the fire, the time-traveler ran his finger along the cold trigger of a revolver.

Nothing about the time-traveler’s appearance seemed out of place; he had been very careful. He was dressed in the manner of the time; his hair was conservatively styled; he was clean-shaven except for a neat mustache. To the club’s other patrons, he was a stranger but not an unwelcome one, and he inspired no suspicion. He might have, had any of them paused to study his behavior more deliberately; the nervous way his right foot tapped against the floor; his sidelong glances at the big door leading to the street; the way his right hand rarely left his coat.

The attendant had noted that the time-traveler had not ordered a drink, which was unusual; however, the attendant knew that the man would wave him over shortly with an inquiry about what kind of gin they had tucked behind the bar. And the attendant was correct; by seven forty-seven, the old man’s anxiety had got the best of him, and the attendant deferred to his solicitous wave and leaned down beside the armchair where the time-traveler sat.

“Something from the bar, sir?” He asked.

“Booth’s, if you have it,” the time-traveler murmured, but he knew they did; he had done his research and kept copious notes.

“Of course,” the attendant replied, and went off to fetch the order.

While he waited, the time-traveler checked his pocket-watch and glanced idly at the old book that he had taken from the shelf. He looked up irritably when the party of four young men entered the library, having checked their coats at the door, which had not opened again since their arrival. The party paused at the threshold to consider the scene before them — the card game going at the table by the wall, the older gentleman beside the bar, and the attendant making the time-traveler’s drink — and then the leader (a tall man in a dark suit) spied the time-traveler sitting in the armchair by the fire.

“I say,” he called, “don’t we know each other?”

For a moment, the time-traveler considered his reply; he had known this was a possibility, of course, had even considered inventing some disguise in order to avoid it, but there had been no time. The answer that he settled on was one he had rehearsed.

“Why no,” he countered, “I don’t believe we do; though I’m known to make an appearance at this club when my business brings me to the city. Perhaps we have crossed paths here before.”

This seemed to halfway satisfy the man, though satisfaction did not have the effect that the time-traveler had intended; the man in the dark suit sat down in the armchair opposite the time-traveler and gestured for his compatriots to go about their business. One went to the bar to inquire about a drink; the others, to watch the card game by the door — slap, slap, slap went the parade of cards on the table as the wagers trundled higher. The man in the dark suit raised a hand to the attendant and then turned back to the time-traveler, who was pointing the revolver directly at him.

Because the revolver was beneath the time-traveler’s overcoat, the man in the dark suit did not recognize his peril.

“What business has brought you to the city tonight?” The man in the dark suit inquired.

Slowly, the time-traveler’s grip on the pistol began to relax. The man in the dark suit seemed to have given up his interest in the time-traveler’s appearance; it was most likely that he had not made the connection.

“I am visiting an old acquaintance,” the time-traveler replied. “One I have not seen in many years.”

The man in the dark suit lit a cigarette and answered, “Perhaps I know him — what’s his name?”

Here, the time-traveler came to a fork in the road, of sorts. He could lie — invent a name that would not warrant a reaction — but a lie would gain him nothing; or he could gamble, and in his heart, the time-traveler was a gambler. The family that he had left behind in his own present — his wife, his half-brother, even his young son — could have testified to this, had they been asked.

Wagering cautiously — not bluffing, not yet — the time-traveler answered, “Charles Bennet Billings.”

The card game in the corner paused — slap, slap, … — and the library was quiet for a moment. The other patrons who had entered with the man in the dark suit looked over at the time-traveler at the sound of Billings’ name. The man in the dark suit smiled pleasantly.

“A friend of yours, presumably?” He asked.

The time-traveler shook his head; he could read the room well enough, even if he had not known the old man’s reputation in the city at this time.

“Not a friend,” he answered.

Two of the three acquaintances of the man in the dark suit had left the card game and now wandered with an air of interest toward the conversation by the fire. The third was standing by the bar and talking with the older gentleman, but even their conversation had sputtered out, and the older man was looking uncomfortably at the floor. One of the other two sat down in a chair beside the fire.

“Maybe you can give him a message for me,” he said.

“Now now,” the man in the dark suit answered, raising a hand to his companion. “We oughtn’t to speak out of turn.”

The time-traveler leaned forward hungrily; for the first time, his hand loosened on the grip of the revolver beneath his coat. “He’s cheated you, hasn’t he?” He asked. “Or he’s welshed out on a deal. Something…”

The man who had spoken began to answer, but the man in the dark suit raised his hand again.

“Coogan here is always a little hasty,” he replied. “But the fact of the matter is that Mister Billings does not have many friends left in his business. It’s true that he has been a patron of this club in the past, but if you mean to find him here, I think you may be disappointed. After last month’s nasty business, I doubt he will return.”

“But he will return,” the time-traveler almost whispered; in his excitement, he nearly showed his hand. “He will come back — tonight.”

The man in the dark suit gave him a puzzled look.

“Am I correct in understanding,” the time-traveler asked him, “that each of you has quarreled with Charles Bennet Billings? It does not surprise me.”

The older gentleman who had been standing at the bar walked out of the library.

The man in the dark suit glanced around at his companions and offered a weak coughing sort of laugh.

“Well really,” he said, “you know it doesn’t do to talk about these things.”

“It does not surprise me,” the time-traveler said again, softly, almost to himself. “And if I knew only what I’d heard — if I had never met the man myself — still, it would not surprise me.”

“Then speak plainly, sir,” the man in the dark suit countered. “What business do you have with him tonight?”

The game was finished; at the table by the door, the men were turning over their cards, revealing secrets.

“Well,” the time-traveler began in a low voice, “because you do not have any love for him — and because you will not believe my story when you hear it — I do not mind telling you the truth. I have come here from the year 2034 to shoot Charles Bennet Billings in the heart. I have come here from the future to murder my own father!”

WHEN THE ATTENDANT returned to the library from the adjoining room, the four regulars were gathered around the time-traveler as he told his fantastic story, and the time-traveler was teetering at the edge of a drunk. He had ordered two more glasses since the time he had begun his tale, and though he had not looked at his pocket watch for several minutes, it was nearly eight o’clock. The attendant knew this, and the two men now at a game of chess at the table by the door knew it too — but the time-traveler did not.

As the attendant set the fourth glass of gin on the desk, the time-traveler put his hand on it without a glance and brought it to his lips; the fire crackled in the hearth, gnawing hungrily at new wood; and the small party of listeners — the man in the dark suit and his compatriots — leaned forward so as not to miss a moment of the tale.

“When I arrived at the decision to destroy my father,” the time-traveler continued after a pause, “the motive proved to be not nearly so complex as the method. My earliest recollections of my father are stained with anger; he resented us — my mother and I — for what we cost him, I think. He had grand designs, supreme ambitions; he thought of us like anchors fastened to his waist, preventing him from his ascension.”

He looked around briefly at their faces.

“I can read your thoughts,” he murmured. “That’s not enough to kill a man. And you’re right, of course — though it felt enough for many years. As I grew older, he grew worse; I often thought of him as a cancer, or a gas cloud, drifting through our house. He would creep, creep in the night, and look in at me with yellow eyes. I tell you there were times that I was sure he was the devil.”

He shook his head, took another drink.

“But we must set aside the nightmares of a child. We must examine the facts. My father was a violent man; he tormented my mother. My father was a trickster; he lied and swindled and played by any means. My father was a thief…”

He glanced at the man who had spoken out of turn before, whose fist was clenched on the arm of the chair.

“… he cheated his partners and cared only for himself. For these reasons, gentlemen, I determined that by all accounts the world would be better off without him. Can I be blamed if it was also what I wanted? And it is best, I think, if I refrained from discussing the things that he would go on to do: the weapon he would build, the great war he would begin.”

“A war?” The man in the dark suit asked.

“A war, that’s right,” was the only answer the time-traveler would give.

At the table by the door, the two men playing chess had stopped the attendant to speak to him in quiet tones, and the attendant’s eyes flicked surreptitiously to the conversation by the fire. The older gentleman had returned to the bar, where he stood by himself and watched the snow fall like ash in the slow night beyond.

“But by the time I’d made my mind up that I should kill him, he had vanished,” the time-traveler resumed. “The modern world is wide, and there are many places for a man like him to hide. I looked for him, I looked for him for many years, before I understood that if I really meant to find him, it would mean looking in the past. You’ll find, I am certain, that it is easier — far easier — to discover where a person has been than to discover where they are. So I began my research, and I began to build my time machine.

“Building the machine was difficult, but not as difficult as the task of locating my father in the past. It quickly became apparent that it would be all too easy to become lost in the thoroughfares of time; so throughout my endeavors, I took detailed notes, documenting my whereabouts — I left maps and markers for myself, to cover for a failing memory. But to realize a person’s specific physical positioning at a precise locality in time is, to put it mildly, more than a day’s work. It cost me; it cost me almost everything. I started with the global tracking data, but our technology companies of course had not arisen yet. I turned to the internet — you won’t understand that word — but there was nothing, no records of him anywhere, as if he had scrubbed his fingerprints from the digi-verse. I hunted down old history books in the attics of abandoned schools, but he had done nothing to warrant an acknowledgement. For a long time, my endeavors grew increasingly desperate, and increasingly fruitless.

“The effort nearly drove us to the gutter — my wife, my son, and I. Think not only of the price of time, but of the monetary cost; our life savings were nearly depleted. When I recollect on that time now, it seems it must have been weeks that I spent searching for the perfect time and place to find him; months that I spent in that basement building my machine; years that passed without speaking to my son. But if the boy were here, tonight, then he would understand: it was all for a purpose; and that purpose was finally achieved.”

The time-traveler smiled thinly, remembering the gamble he had made earlier that evening. He looked at the companion of the man in the dark suit; the one who had bristled at the mention of Charles Bennet Billings’ name: Coogan.

“It was you,” he continued, raising a finger to the man who sat across from him. “You, who led me to him, in the end.”

Coogan exchanged a troubled glance with his compatriots, not understanding the implication. The man at the dark suit narrowed his eyes minutely, waiting for the time-traveler to resume. After another moment of suspense, of course, he did.

“At great cost, I had acquired a collection of vintage newspapers. I don’t know how long I waded through them, looking for those three words:

“Charles.

“Bennet.

“Billings.

“Finally, I found him. You can’t perceive the feeling of revelation. From October twenty-seventh, nineteen sixty-four, a small headline buried on page seven of the Manhattan Mercury: Social Club Calamity: Charles Bennet Billings Assaulted By Ex-Partner Coogan At St. Jude Club, Manhattan.”

Coogan said nothing, but his face had gone as white as a sheet.

“As I mentioned earlier,” the time-traveler replied, as if Coogan had spoke, “he will return — tonight.”

The time-traveler turned to face the man in the dark suit, continuing a conversation that had only been deferred.

“When I mentioned my father’s name, your friend was quite excited. Well Mister Coogan is going to assault Charles Bennet Billings when he walks through that door in exactly…”

He looked at his pocket watch.

“… two hours, eighteen minutes. They will argue, they will fight, and in two days the story will be printed in the newspaper — a newspaper that will survive for seventy years, to be found by a man looking for a needle in the past.”

Beneath his coat, the time-traveler ran his finger along the cold metal of his pistol.

“Only none of that will happen,” he said, “not this time. This time, Mister Coogan, you will leave the St. Jude Club before 11pm, you will spend the night in your own bed instead of the city jail, and you will say nothing about the man you met at the club tonight, with his wild, silly stories. And Charles Bennet Billings will answer to me. Finally, he will answer to me.”

While the others sat across from him, mute and shellshocked, the time-traveler turned his gaze away from his audience and the fire, his tale completed, his intentions firm.

“And me… I’m out there, too” he said softly, looking through his pale reflection in the window and out into the dark, bewildering night. “Out there right now, somewhere in the city: five years old, seven months, six days. Only a child — oh, what I would say to him, if I could see him.”

Outside, the snow fell like sand in an hourglass; inside, the fire chewed the logs like time.

DURING THE ONE HUNDRED and eleven minutes that dripped by like water from a faucet after the time-traveler had finished his account, the club settled into a watchful reverie. The older gentleman at the bar, after a last drink, made his final exit. One of the two chess-players at the table by the door lured the other into a rook and pawn endgame, and between curtains of violence, they departed. The attendant moved like a ghost between the bar, the kitchen, and the library, stoking the fire and offering a soft goodnight to each of the men as they retired. The snow had softened to a light veil; the fire had turned toward sleep among the bones of its collation.

One by one, the time-traveler’s audience had drifted off like satellites: to the game room, to the bar, and then finally out into the riddles of the night. Only Coogan had paused for a moment before setting off into his unknown future — maybe fidgeting with words of gratitude, or haunted by a roost of mysteries — and then departed without saying another word to the time-traveler, who now sat alone beside the seething embers.

Lost in his own reverie, the time-traveler started when a voice called out across the room,

“Well then, I’m off!”

The man in the dark suit was standing by the door, one arm in his coat, the other raised in a quaint farewell.

“I wish you all the luck in the world, my friend,” was all he offered, “but you’re either a madman or a murderer; I don’t have any wish to associate with either one. I’ve got two daughters and a son at home, and they’ll be waiting up for me.”

The time-traveler smiled softly through the warm curtain of gin and anticipation.

“Buy a copy of the Mercury tomorrow, if you’d like,” he said, “and you’ll find the truth out for yourself.”

The man in the dark suit smiled painfully, gave the old time-traveler a final nod, and then raised a hand to the attendant by the bar.

“By the way, my friend,” he called to the attendant, “where’s old Holloway tonight? I meant to thank him for his help with the sherry spill last evening.”

The attendant informed the man in the dark suit that Holloway was under the weather with a head-cold and had taken the night off, and the man in the dark suit thanked him and said goodnight and then disappeared into the snowy evening. Had he turned left and walked into the alley behind the St. Jude Club, he would have found Holloway — the usual attendant — hidden behind the dumpster with his mouth and hands wrapped in silver tape and his nose frostbitten, shivering in the dark. Instead, the man in the dark suit turned right, heading uptown toward home, and a few minutes later he passed Charles Bennet Billings who was walking down from the office for a nightcap at the club. He hesitated for a moment, almost spoke to him, but soon the man had disappeared down the street, only a lost shape in the dark.

In the library, the fire had burned out. The time-traveler, sitting in the armchair by the window, checked his pocket watch and noted that in three minutes, Billings would arrive. He shivered against the biting wind that blew in through in the window, and gestured for the man dressed as an attendant to come and light the fire. The man dressed as an attendant bowed and knelt beside the hearth, kindling young flames that would burn above the gravesites of their parents.

“You know, I know what it’s like to have an axe to grind against your father,” the man dressed as an attendant offered softly, not yet turning to face the time-traveler.

Behind him, the time-traveler made a distracted, noncommittal noise.

“My father was also an ambitious man,” the man dressed as an attendant continued. “Consumed by his obsessions. When he left, he left nothing for me, nothing for my mother.”

Behind him, the time-traveler had begun to stand, his hand tight around the handle of the pistol, his eyes dancing from his pocket-watch to the foyer and the door.

The man dressed as an attendant turned. “Fortunately, he did leave detailed notes behind: the blueprints to his machine; where he had been, where he was going; where he could be found on certain nights.”

The old time-traveler had taken three steps toward the door before the next words stopped him like a broken clock, frozen in time.

“But of course, my father was a gambler,” the young time-traveler dressed as an attendant said, removing a small revolver from his jacket. “And gamblers never think ahead.”

Understanding everything at last, the old time-traveler turned to face his son, who was dressed as an attendant and holding a revolver at his waist, pointed at his father.

The door to the club opened and Charles Bennet Billings entered, paused, stood breathless in the doorway.

The next morning, a young couple would report to the Manhattan Mercury that they had been passing by the old brick building sometime around eleven o’clock at night when they had heard a single gunshot, then a strange sound like a heavy wind — it was the sound of a young fire burning down to embers and a time-traveler vanishing into the night.